News

Rice University develops method to convert hydrogen sulfide into high-demand H2 gas

Rice University engineers and scientists have created a sweet way for petrochemical refineries to turn a smelly byproduct into cash.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas has the unmistakable aroma of rotten eggs. It often emanates from sewers, stockyards and landfills, but it is particularly problematic for refineries, petrochemical plants and other industries, which make thousands of tons of the noxious gas each year as a byproduct of processes that remove sulfur from petroleum, natural gas, coal and other products.

In a published study in the American Chemical Society’s high-impact journal ACS Energy Letters, Rice engineer, physicist and chemist Naomi Halas and collaborators describe a method that uses gold nanoparticles to convert H2S into high-demand H2 gas and sulfur in a single step. Better yet, the one-step process gets all its energy from light. Study co-authors include Rice’s Peter Nordlander, Princeton University’s Emily Carter and Syzygy Plasmonics’ Hossein Robatjazi.

“Hydrogen sulfide emissions can result in hefty fines for industry, but remediation is also very expensive,” said Halas, a nanophotonics pioneer whose lab has spent years developing commercially viable light-activated nanocatalysts. “The phrase game-changer is overused, but in this case, it applies. Implementing plasmonic photocatalysis should be far less expensive than traditional remediation, and it has the added potential of transforming a costly burden into an increasingly valuable commodity.”

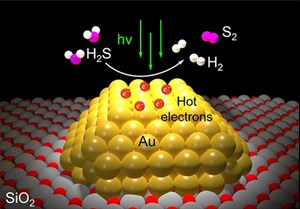

Each molecule of H2S gas contains a pair of hydrogen atoms and one atom of sulfur. Each molecule of clean-burning H2 gas—the staple commodity of the H2 economy—contains a pair of H2 atoms. In the new study, Halas’ team dotted the surface of grains of silicon dioxide powder with tiny islands of gold. Each island was a gold nanoparticle about 10 billionths of a meter across that would interact strongly with a specific wavelength of visible light. These plasmonic reactions create hot carriers, short-lived, high-energy electrons that can drive catalysis.

In the study, Halas and co-authors used a laboratory setup and showed a bank of LED lights could produce hot carrier photocatalysis and efficiently convert H2S directly into H2 gas and sulfur. That’s a stark contrast to the established catalytic technology refineries use to break down H2 sulfide. Known as the Claus process, it produces sulfur but no H2, which it instead converts into water. The Claus process also requires multiple steps, including some that require combustion chambers heated to about 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

The plasmonic H2 sulfide remediation technology has been licensed by Syzygy Plasmonics, a Houston-based startup company with more than 60 employees, whose co-founders include Halas and Nordlander.

Halas said the remediation process could wind up having low enough implementation costs and high enough efficiency to become economical for cleaning up nonindustrial H2 sulfide from sources like sewer gas and animal wastes.

“Given that it requires only visible light and no external heating, the process should be relatively straightforward to scale up using renewable solar energy or highly efficient solid-state LED lighting,” she said.