News

At least 20 hubs submitted final applications for U.S. H2 hub funding

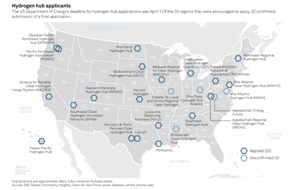

At least 20 groups from across the U.S. have submitted final applications to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) hoping to receive up to $1.25 B in federal funding and become one of six to 10 clean H2 hubs, according to a survey conducted by S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Following the DOE’s April 7 application deadline, the agency declined to reveal any information on the applicant field – neither the identities of the groups that had submitted applications by the deadline nor the total number of applications received.

“The department will release more information on selected applications following the merit review process and selections announcements,” a DOE spokesperson said, adding that hubs were expected to be selected for award negotiations in the fall.

However, most of the hub hopefuls have self-identified as candidates, either via press releases or in conversations with S&P Global. Of the 33 hubs that received notices of encouragement from the DOE in January, 20 confirmed application submission, two hubs merged, two hubs did not respond to inquiries, and two more declined to confirm or deny application submission. The status of several others remains unknown.

The April 7 deadline concluded what had been a challenging chapter in the hub selection process, which was initiated in November 2021 when President Joe Biden signed into law the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

“The application process was just so aggressive, so fast,” said Jeff Pollack, who helped lead the Horizons and Trans Permian Clean H2 Hub application in Texas. “There was so much work required in modeling. In order to meet that April 7 deadline, you really had to lock in a governance structure and a management structure very early in the process in order to be able to do the techno-economic modeling that was required. The process was just inherently challenging.”

The known field of 20 applicants reveals an menu of hubs that propose to focus on a diverse array feedstock. While the Horizon and Trans Permian hub—which would connect the Permian Basin to the Corpus Christi port—aims to produce 1,900 MMtpd of mostly green H2 by 2030, the larger HyVelocity Hub, also on the Gulf Coast, would produce about 9,000 MMtpd with a color agnostic approach.

The two hubs proposed for the Pacific Northwest would leverage the region’s considerable hydroelectric resources, while the hub proposed for the California region, the Alliance for Reliable Clean H2 Energy Systems, or ARCHES, would focus primarily on green H2.

And in the Midwest, the Great Lakes Clean H2 Coalition aims to leverage Energy Harbor’s nuclear power station in Ohio to generate 100 MMtpd in the near term, then focus on solar power-based H2 in the long term.

“I can’t really go into the proprietary information, but our plan is to start with a 2-MW system, perhaps as early as 2024, to beyond 250-MW production at the [Energy Harbor] site,” said Vice President of Research Frank Calzonetti of the University of Toledo, a partner in the Great Lakes hub. Then “the idea is to produce additional H2 using solar energy.”

Phases. The ultimate winners of the H2 hub selection process may not be ultimately known for some time. According to the DOE’s funding opportunity announcement, the application period that concluded on April 7 leads into the first phase of the selection process, in which the DOE will dole out up to $20 MM to hubs with a 50% minimum cost matching requirement following the merit review process. That phase will span 12 to 18 months.

Then, awardees move into a negotiated go/no-go process before moving into phase two, where they can receive up to 15% of each hub’s total requested amount. This phase can take up to two to three years.

Once in phase three, the DOE will begin releasing the remaining 85% of federal funding on an undefined schedule while closely monitoring each hub’s implementation process – a stage that could take two to four years. In the final fourth stage, hubs will transition to their operational stage.

“At the end of the day, what the DOE is trying to do here is build a nationwide network, and it’s incumbent on all of us who have an interest in its value chain to think about ways to work together, even with entities with whom we may feel we’re in competition with now,” Pollack said.